‘The rug can be pulled any time’ – how indie music has adapted during Covid

This was supposed to be Arlo Parks’ year.

The soulful indie singer was named on the BBC Sound of 2020 list, had her first UK headline tour under way and support slots in the States lined up, not to mention Glastonbury.

But before spring had sprung, she saw those plans “dissolve before my eyes” due to the “devastating” pandemic.

“I think I did have a fear that it was going to seriously rock my career and prospects,” says the 20-year-old Londoner, who is signed to independent label Transgressive.

“It’s shown that the rug can be pulled from under my feet at any time.

“But then on the flip side, I did learn that sense of resilience and finding ways to stay connected with fans and maintaining a sense of inspiration, and just doing my best with what was available and remaining optimistic.”

The Association of Independent Music Award winner says the pause has given her time to write and enjoy some “surreal” experiences – like playing in an empty church with Phoebe Bridgers, and performing to a bunch of cows at Glastonbury’s vacant Worthy Farm.

“I think taking time to just focus on my craft – learning to make beats, playing guitar, writing poetry and reading – getting back to the crux of like what makes me an artist, which is the actual creation process, has been my focus day-to-day,” she says.

“Then I guess trying to remain optimistic that gigs will come back at some future.”

Parks is among the indie artists helping BBC Radio 6 Music celebrate and examine the scene on its State of Independents Day on Thursday.

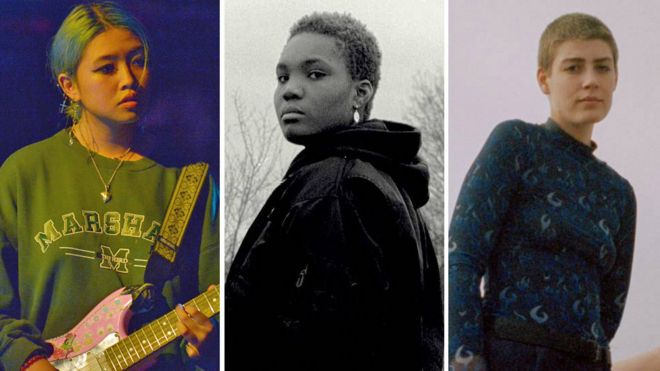

Another rising star whose ascent has been slowed by the virus is fellow Sound of 2020 act Beabadoobee.

The 90s-influenced rocker, real name Beatrice Kristi, says it “kind of sucked” to miss out on opening up for her Dirty Hit labelmates, The 1975, at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

Instead, she used confinement to live-stream bedroom gigs on social media, and create the “perfect aesthetic” for her debut album, Fake It Flowers, which drops next month.

“I wouldn’t say I didn’t miss out on anything, but we have so much time and it’s nice to take some things slow,” offers the 20-year-old, who has a rescheduled tour booked in for September 2021.

“In all honesty, I feel like if I went away for this whole year – I didn’t think I was ready. Now I think I’m ready, because I’ve spent so much time with my family and my boyfriend and I’ve kind of grown up a bit.”

‘Cultural recovery’

While socially-distanced indoor gigs have been allowed in England since mid-August, most venues have been unable to put them on in practice.

The Brudenell Social Club in Leeds has seen shows pushed back until next spring, but owner Nathan Clark tells the BBC those dates are only provisional.

The Yorkshireman is one of many grassroots venue bosses waiting to see if they will benefit from the government’s £1.57bn Culture Recovery Fund, of which £3.36m has been set aside for music venues.

Culture secretary Oliver Dowden told The Mail on Sunday that “mass indoor events” like opera, ballet and classical are now in sight. Yet Clark believes greater “sector specific support” is required to make it feasible for the live independent music circuit to re-start.

He notes how the guidance for “someone going to a theatre to sit down and observe quietly with their arms crossed” is not applicable to those going to see a rock band, rapper or DJ.

“You go to a gig to interact with people,” says Clark. “To enjoy the music, dance and sing along. You can’t do any of that, so it’s taken away the main point of it.

“We’re starting to get back to arranging some types of events and finding ways to make it work,” he goes on. “But it’s not going to be live music as we know it. It’s going to be quite weird for a long time and it’s certainly not going to be worth any money for us, for the artists, or for anyone else.

“It’s basically an exercise in seeing, can we do it? Can it support a cultural recovery?”

‘Normal jobs’

Brighton-based guitar band Porridge Radio emerged from the rubble of 2020 after their second album, Every Bad, was nominated for the Mercury Prize.

Fittingly, it finds frontwoman and main songwriter Dana Margolin reflecting on feelings of frustration and uncertainty.

Plans for the four-piece to quit their “normal jobs” to chase the music dream full-time have had to go on hold for now, which she believes may have worked in their favour during the crisis.

“I think for us, we don’t have this sense of entitlement to a job in music,” says Margolin, who also works as a nanny. “It’s quite new for us anyway, for things to be going well!

“We’ve not played any of our sold-out shows,” she adds. “It just didn’t happen. So I’m like, ‘Oh well, does it really exist?'”

‘Music is a product’

Tom Gray’s band Gomez won the Mercury Prize in 1998, when it was possible to stage an award ceremony.

Gray, now a director of copyright collective PRS for Music, says Southport’s finest would have “no chance” of making a living from music in today’s landscape, partly because streaming royalties don’t go far when split five ways.

With gig earnings virtually cut off overnight, most artists have found they can no longer fall back on income from recorded music. Gray has launched the Broken Record campaign, calling for streaming giants like Spotify and YouTube to change their “outdated” models and pay artists more fairly. According to CNBC last year, rights-holding artists on Spotify earn around $0.006 (£0.0051p) per stream.

“Recorded music is a product; it’s a thing that we make and we spend months and years of our lives making it,” says Gray.

Gray stresses the “narrative” that independent musicians earn as much as megastars like Adele or Stormzy needs to change too. “These people live in your communities, they play in your pubs, they probably make your coffee,” he says.

‘Consumption stronger than ever’

North west-based indie label Nice Swan Records offer “artist-friendly 50-50” record deals to the acts that come through their stable, such as Mercury Prize nominees Sports Team, Pip Blom and Fur.

The two-man operation, comprising Alex Edwards and Pete Heywoode, have also had to cancel tours this year and delay album campaigns for their more established acts, some of whom have had to take advantage of furlough schemes and other funding.

However, they found that launching an “introducing” series, highlighting their new signings during lockdown, brought great exposure.

“It’s been really exciting launching new careers and getting loads of coverage in the media and press and radio,” says Edwards. “But obviously with more established acts that are going into album two and three, we’ve hit some brick walls.

“We’ve noticed streaming figures going up,” notes Heywoode. “The consumption of music has been stronger than ever.”

The pair will continue to put their artists’ material on streaming sites, and in independent record shops.

Phil Barton, who manages the Sister Ray shop in central London, says they had a “brilliant” Record Store Day last month.

They shifted most of their stock via a mixture of in-store and online sales, which he says was “a shot in the arm” after “a really bad six months”.

He thinks smaller record shops can help themselves by having an online presence. He’d also like to see some external help so they can continue to enable people to “make contacts, exchange ideas” and discover their own Arlo Parks, next year and beyond.

“I think record stores should come under the same sorts of banner as live venues, and they should be treated as a sort of cultural necessity,” states Barton.

“If we are to save as many record shops as we can, then maybe we should make it very difficult to close them down.”